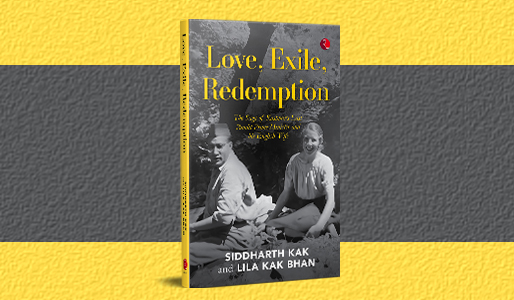

Love, Exile, Redemption: Free Read | Chapter 7: Falling in Love

Falling in Love

History and circumstance had an important role to play in the meeting of my parents—Bhaiji and Bended—and the cementing of their relationship in England. My father visited London for the first time as part of the Maharaja’s official delegation to three round-table conferences held in 1930, 1931 and 1932. This was fortunate because it was only in the previous year that he had been transferred from the archaeological to the political department. The Maharaja, it is said, delivered an electrifying speech on behalf of the princely delegation at the first round-table conference. Since travelling to England was time consuming and cumbersome—about three weeks each way—when the delegation reached London, it stayed for a few weeks, sometimes a few months, before returning to India.

My mother had done a secretarial course, in addition to her BA in English and nursing degree. Once she resigned from her job at St Thomas’ Hospital, she decided to work in India House just for the duration of the round-table conferences my father was attending from 1930 to 1932. Colonel K.N. Haksar—who served as a senior member of the Chamber of Princes, with offices in the Savoy Hotel—was in charge of interviewing and appointing staff. He hired my mother as a secretary.

The whiskered and courtly Colonel Haksar was quite a charming gentleman for the ladies. It was he who first took my mother to see St James’ Palace, otherwise not accessible to ordinary folk. Haksar also, it is believed, took his staff, mostly composed of women, out to a nightclub. One of them was apparently quite sweet on him. My mother told me that she admired Haksar but more from the point of view of exoticism. My father, however, gave her quite a lot of that. He humorously recalled that perhaps that was why she transferred her attention to him!

Before my mother was assigned to the post, my father’s secretary in England was a cousin of Sir Dinglefoote, a Member of Parliament from the Labour Party. One day, while returning to his hotel, my father spotted her walking along the kerb near Piccadilly Circus. Since he had some instructions to give, he stopped the car, leapt out, spoke to her for a few minutes and left. My father, apparently, presented quite a picture on the busy streets of London, as he was wearing tight white pyjamas (Jodhpurs), a black achkan and a flaming red turban. No doubt he wore his clothes well, even the humblest variety. His secretary later informed him that he had accosted her near her college, where several of her friends had been hanging out of the window and seeing the episode had got greatly excited, questioning her no end about the Indian raja she was keeping company with!

Sometime after this incident, Colonel Haksar asked my mother if she would work for my father while he was there for the round-table conferences. She agreed on the condition that she would be allowed to leave if she got a permanent job elsewhere. Haksar’s responded to this saying, ‘Well I don’t suppose he will break his heart over it!’ But, by the time my father returned to India in 1931, it seemed probable that he would! There was an interest on both sides, but it was nothing too serious. They began an initial correspondence.

This is how my parents met and were drawn to each other, cementing their acquaintance over the years of the conferences, starting in 1931 and later, through a prolific correspondence—a relationship that finally culminated in marriage. In the early years, when my mother’s father opposed the relationship, she would destroy my father’s letters after reading them. Finally, after five long years, her father told her, ‘For goodness sake, marry him or break it off!’

When they first met in 1931, my father asked my mother out to watch a film. It was apparently a noteworthy event for him. I am intrigued by this recollection because, to my knowledge, I do not recall my parents ever seeing any films in later years. I have often wondered what they did outside work. I know they would go for the occasional plays and see some of my mother’s friends and relatives.

Their relationship wasn’t all smooth sailing by any means. My father was 37 years old when they first met. He was a widower with four sons and a daughter (his niece, in actuality, whom he took as his own after his favourite sister’s death). He was in a responsible job, on an upward trajectory in the Government of Kashmir and devoted to his family. My mother was 25, young, charming and very friendly with her sister-in-law’s brother—a solid army officer from a well-established family like hers. It was all ‘just right’, which was a strong consideration in those days. She broke off her engagement with the army officer after she met Bhaiji at the consecutive round-table conferences because his unusual personality and levels of interest were very appealing to her. She decided to introduce him to her family.

The introduction of my father to the Allcocks is predicated on a rather hilarious incident. When my father went to Loughborough to spend a night and visit the family, a splendid spread had been prepared for high tea. Five o’clock rolled around and my grandfather, great-aunt, father and mother gathered round the table. Everyone, except for Bhaiji, filled their plates and tucked into the delicious offerings. They continually offered the various meat pies (carefully omitting any beef), scones, a delicate array of pastries and, of course, cheeses to my father. My father took an exiguous serving despite everyone pressing him to have more. After a couple of hours of pleasant conversation, it was bedtime. My mother took him up to his room, where he found a cup of hot milk and some biscuits, neatly arranged on a beautiful bone china plate next to it, along with a container of Horlicks. Around 9.00 p.m., as my mother was at the door, about to go to her room, he suddenly sprung a question at her, ‘Don’t any of you eat dinner?’ My mother was surprised and responded, ‘Of course we do. What do you think all the delicacies at high tea were? We kept pressing you to have some, but you scarcely ate anything.’ He was really hungry by bedtime, but all the food had been cleared away and my mother jokingly told him, ‘Next time, eat when you see everyone else enjoying the food! We were all imploring you to eat!’ In India, dinner is served late, often at 9.00 p.m. or 10.00 p.m., sometimes even later. In England, it is done by 6.00 p.m. or 7.00 p.m. at the latest! This remained a private joke for decades.

Another observation that my father made was the long duration of baths in England. He told my mother how unhygienic he thought it was to ‘Wallow in your own dirty and soapy water!’ He dealt with this by using his shaving mug—which was usually home to his bristle shaving brush, shaving soap and razor—to pour a few mugfuls of ‘clean’ water over himself before emerging from the bathtub!

Bathrooms featured prominently in my father’s list of priorities, since he had a Brahminical attachment to bathing and cleanliness. This led to an unexpected crisis at the Savoy Hotel, where he was staying. He found some strange basins and gadgets in his bathroom; he twiddled some knobs and taps to no effect before leaving the bathroom, bewildered. A few hours later, he went to answer a furious knocking on the door. When he opened it, a gang of plumbers fell in, gasping, ‘What have you done? You have flooded the whole dining room!’ Apparently, while twiddling the gadgets, he had inadvertently opened an internal tap and the water had leaked through the ceiling of the lower floor and had begun to drip on to the dining room tables below.

London was a cultural learning experience for my father over the six years he happened to visit it for the round-table conferences and later for the King’s coronation. The first time he came, he stayed at the posh Mayfair Hotel in central London. All his bills went into his room account and to settle them at the end, he gave a tip of only half a crown or five shillings at that time. Remembering this act caused him great embarrassment later, when we realised how disproportionately small the tip had been to the bill. Similarly, while staying in an exclusive flat on St James’ Street, where he first met my mother, with St James’ Palace at the end of the road, the manageress, Mrs Collins, came up to have a word with him about leaving his money and change on his dressing table, which was likely to be pinched. My father, thinking perhaps of his house full of faithful retainers in Kashmir, said that he would not complain if his money was pinched. Mrs Collins replied, ‘Well I don’t mind if you don’t love money, but the girls who work here are poor people and it is unfair to expose them to the temptation.’ Thereafter, he never left his change outside on the dressing table.

These cultural differences never came in the way of my parents’ relationship. In fact, they cemented their understanding and love further, becoming the basis for a humorous and much deeper understanding of the commonalities that we all need to recognise in one another. I remember many occasions when they teased each other about such funny incidents! I was blessed to grow up in such a harmonious and loving atmosphere.

My parents were both very open with each other right from the beginning. While Bhaiji was very clear that his children’s welfare was his primary occupation at that point, he was also certain that he loved my mother deeply and dearly. He suggested she visit Kashmir and meet his family. He wanted my mother to see for herself if she would be able to accept a dramatically new culture and way of life and make it her own. Not only would this give her a clear idea of what her life in Kashmir would be like but would also, very importantly, give his family time to meet her and come to terms with his decision. He might not have been a very demonstrative man, but his actions clearly showed his concern for my mother, his children and his immediate family. After nearly seven years of courtship, amid many agonising moments of ‘Will it work?’ or ‘There’s no one I’ve loved more, or by whom I have been as intellectually stimulated’, their trust and love prevailed.

One day, on my father’s invitation, my mother decided to travel to India and introspect if she really wished to adopt this man, his family and his land as her own. It was a leap of faith. ‘Billa,’ Mummy once called me, using her special name for me which is a derivative of Billy, ‘despite all the troubles we have had to go through, I would choose to live my life the same way again, with your father.’

This statement is an amazing testimony to my father and mother’s relationship. I can see her and hear these words clearly as I write them. They truly were the most compatible couple I have ever known. Who made more adjustments? Was it the times? Whatever it was, it led to an amazing partnership. I am not exaggerating when I say I cannot recall an argument between them. They were very democratic, and listened to and respected each other’s opinions. They gave and took advice and shared so many interests! In a moment of loving indiscretion, my mother confided in me, ‘London was strewn with our kisses,’ for they had had six years of courtship!