A Refugee Who Built a Business Empire

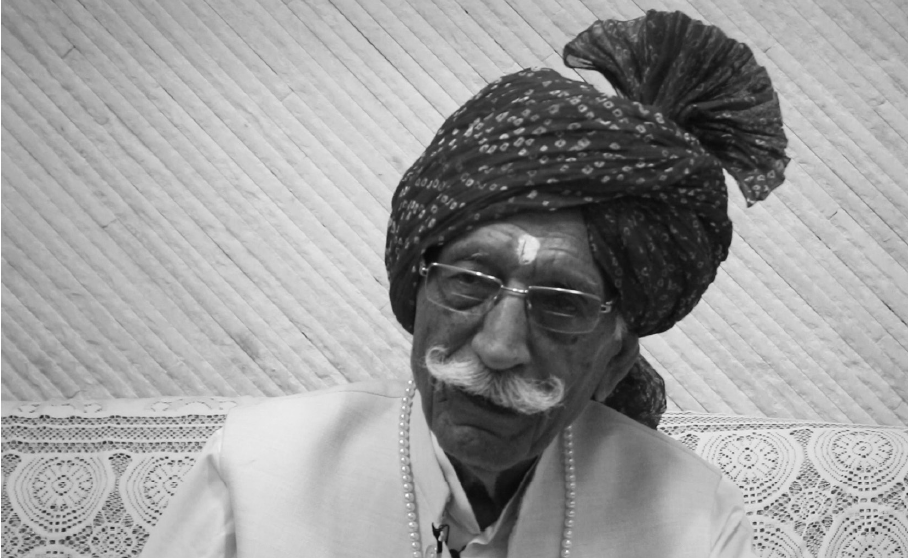

Dharampal Gulati

Born: 27 March 1923 in Sialkot, undivided Punjab

(now in Pakistan)

Dharampal Gulati is perhaps the most recognized grandfather on Indian television, as he appeared regularly in the advertisements for his company, MDH Masalas. A fifth-class dropout, Dharampal has outwitted the CEOs of other consumer goods companies to create a spice empire valued at around Rs.1,000 crore.

Here’s his story, extracted from Mallika Ahluwalia’s book Divided by Partition: United by Resilience

Ninety-five-year-old Dharampal Gulati is amongst the highest paid Chief Executives in India, according to newspaper reports from early 2017, which pegged his salary at `21 crores in the previous year. He did not, however, start his life in easy circumstances. The roughly `1,000-crore masala empire he has built has been a result of his sheer business acumen and

perseverance.

He was born in Sialkot (now in Pakistan) on 27 March 1923 to Chunnilal Gulati and Channan Devi. Living in a joint family, with two brothers, five sisters and seven cousins, Dharampal remembers a childhood of much love and play. It was a down-to-earth, rustic life as the family was not very wealthy. Dharampal remembers taking care of the two buffaloes, mornings at the akhada (wrestling ring) and the joy of eating his mother’s home-cooked food.

At age five, he was enrolled in the local Arya Samaj school. But he was not very interested in studies and dropped out of school of his own will at a young age. ‘I could never concentrate on my studies.’ He recalls an incident from the fifth class when his English teacher pinched him for not knowing the answer to a question—for Dharampal, that was the end of his formal education. ‘I decided that studying is very difficult and I didn’t go back to school from the next day.’ He had not even taken his fifth class examination.

‘I used to play, I used to fly kites and pigeons and slowly I got older. My father asked me, “What will you do? How do you plan to become successful in life?”’ Dharampal started experimenting with different trades. He tried carpentry, soapmaking, working with glass, cloth trading, working with a goldsmith, but he couldn’t stick with anything.

The family business was spices. Dharampal started working in the shop that his father jointly ran with his brother. The shop was called ‘Mahashian di Hatti’, and it was in a local market called Bazaar Pansaariyaan in Sialkot. He would help out with everything, making packets of spices, or taking small pouches of mehndi for door-to-door sales. The family was renowned for a special spice—deggi mirch—and Dharampal took on the role of salesperson. ‘I went to Wazirabad, Majitha… I expanded the business to Lahore. From Lahore, we expanded to Sheikhupura and after that to Nankana Sahib, then to Lyallpur and then till Multan.’ The shop’s sales grew rapidly, and Dharampal recalls that sales reached between `500–800 per day—a large sum

in those days.

At one point, Dharampal’s father, Chunnilal, helped to set up a shop for Dharampal and his brother, Satpal. However, the location of the shop was such that it proved economically unviable. They ultimately shut it down.

Around this time, in 1942, Dharampal got married at age 18 to Leelavati. Tragedy would strike the young couple when their first two children passed away as infants. Little did they know the many challenges fate was still going to throw their way.

Life then still consisted of simple pleasures. Dharampal remembers the excitement when during World War II, a neighbour got a radio. The entire neighbourhood would gather in this person’s house to hear the news on this still-rare contraption. However, soon they would hear much grimmer news close to home.

Dharampal and his family had no idea that they would have to leave their own land and home to go to a new city with which they had no ties, where they knew no one, where the way of speaking, the culture, the customs would all be different. It is very difficult for a family of ordinary means to think about leaving their ancestral home and their business. However, the

escalating riots in Sialkot in 1947 made it impossible to stay.

‘Every night we heard the shouts of Allah hu Akbar, Har Har Mahadev.’ Then one day, their neighbour’s house was set on fire by a mob. Some people came to Dharampal’s father and advised him to leave. On the night of 14 August 1947, instead of the fireworks of celebration, the family could see the orange glow of so many homes and businesses going up in flames. For families that had spent a lifetime building their factories and homes, to lose everything overnight was devastating.

On 20 August 1947, the family moved to a refugee camp. ‘We didn’t bring anything, just a little money,’ remembers Dharampal. They had given their buffalo to their Muslim tailor, who in turn helped them recover some cash lying at their shop.

A few weeks later, on 7 September, as the situation got worse, they decided to leave the camp for Amritsar. They managed to get to the railway station in Sialkot on a military truck, and from there took a train the following morning for Amritsar. As the train passed stations like Pasroor and Narowal, they could see mobs gathered, and their fear kept rising. Finally, they reached the border town of Jassar, across the Ravi river from Dera Baba Nanak. At the river, the stench of corpses was unbearable; everywhere around them was death. ‘Our train reached safely but in the train that came behind us, everyone was killed.’ In the pouring rain, with great difficulty, the family crossed the bridge on the river Ravi, moving finally from Pakistan to India.

That night a grievous tragedy befell them. While they were sleeping near the railway tracks, a military truck accidentally drove over his uncle’s leg. ‘His leg broke. We spent the night crying.’ In the middle of the night, in an unknown place, the family was at a loss to know what to do. They managed to make their way to a nearby hospital, but realized that there were no medicines or doctors there. Fortunately, the following morning a truck from Amritsar came bearing food for the refugees, and the family was able to transport their uncle on this truck to the Civil Hospital in Amritsar.

The fracture was severe—the doctors had to put both steel implants and weights inside to straighten it. His leg was also put in a plaster. It would eventually take more than three months for his leg to heal.

By 27 September, Dharampal realized that it was difficult to find work in Amritsar. He and two of his relatives decided to go to Delhi, while the rest stayed back in Amritsar with their injured uncle. Their train to Jalandhar stopped midway as a bridge had been washed away due to the heavy monsoons. They made their way partly on foot, partly by truck to Ludhiana, where they found some relatives who had also come from across the border, and who were now staying in a house evacuated by a Muslim family. The following morning, they left for Delhi to find one of Dharampal’s sisters, who was in Delhi as her husband had a government job. Dharampal remembers the mayhem: ‘People were sitting on the roofs of trains because there was no space inside, but none of them knew that there were so many tunnels—a lot of them fell off when the train would go through tunnels. They died. The train was moving very slowly and we reached Sabzi Mandi station in Delhi at 4 a.m. the next morning. I had only `1,500 in my pocket,’ he remembers.

Dharampal had heard of Delhi many times on the radio but he had never been there. They got off at the railway station and made their way on foot to Karol Bagh to find his sister.

She had managed to claim one of the abandoned houses in that area for them—a broken down, ramshackle place. ‘It was a small house with hardly any place to sleep. There was no running water, no latrine.’ Staying in this place was difficult, especially given the heavy rains that seeped through the broken roof areas into the room. But it was a shelter nonetheless. Dharampal and his two relatives moved in there.

Dharampal remembers that it was here in Delhi that he heard his new moniker—‘refugee’. He went to the government office and registered the family details, and in return was given a refugee card that entitled them to basic rations.

‘I was wondering what I should do… One day, while roaming around, I reached Chandni Chowk. People were selling tangas (horse carriages) there. I asked them how much they were selling for. I bargained a little bit and finally got a tanga for `650.’ Dharampal had decided that he would try to earn his livelihood as a tanga driver, while also taking the opportunity to acquaint himself with his new hometown. ‘I used to wait near the railway station and say “two annas sawari, two annas”. I would observe the other tangawallahs and then shout out neighbourhood names, like “Karol Bagh, two annas, Karol Bagh, two annas”. However, Dharampal soon realized that he was not enjoying this new profession. He found the other tangawallahs uncouth, and the work draining, with little monetary reward.

He then tried opening a small stall to sell cane sugar, but he saw no prospects in this either, and soon shut it down.

More and more relatives started arriving, particularly his parents and the rest of the family who had stayed back in Amritsar to be with his uncle till the leg healed. Their little house was soon overflowing with extended family members, but they could not turn anyone away.

The family was struggling to make ends meet. Despite an initial hesitation about going back to spice trading, Dharampal soon realized that this was the trade they knew best and that could help them find their feet again.

They started with a small wooden roadside shop.

Life was tough. Dharampal remembers that the lack of a latrine in the house meant that they would have to queue up each morning at a public municipal latrine. The family had to live frugally, especially given the large extended family that had joined.

To grow the business, he put an ad in a popular Hindi newspaper, Pratap—‘Mahashian di Hatti of Sialkot Deggi Mirch Waale’.

This proved to be a winning solution. Within days, they started getting numerous orders by mail. One of the first was all the way from Cuttack in Odisha from a businessman who had migrated from Multan.

The business started growing. Dharampal decided to open one more shop in the main spice market in Delhi, Khari Baoli, and then soon another. Meanwhile, they had also put in a claim with the Ministry of Rehabilitation for the shop and property that they had left behind in Sialkot. They were allotted a plot in Gaffar Market.

Dharampal would work 12 to 15 hours a day to ensure that the business could establish itself and grow. These long hours put a strain on his health. By 1952, he had developed sciatica. The pain was so intense that for many months, he was almost completely bedridden. But he persevered.

Throughout this time, Dharampal put a strong focus on ensuring a high quality of his products. In a new city, with no business relationships, or known suppliers, he had to struggle to find the right partners. He went through quite a few bad experiences—for example, he discovered one of his suppliers was adulterating his spices with lentils to lower costs. Dharampal immediately broke the business relationship; he was quite clear that standards had to be fully maintained and exceeded. He also had the novel idea in 1949 of packaging spices in well-designed boxes. Some of the designs created in 1949 last to this day.

By 1954, the business had grown enough that the family could afford to buy their own house. This was just the start of a long journey that would see Dharampal establish his own factory in the 1960s, and go on to achieve milestone after milestone in business growth. Today, the MDH empire is valued to be around Rs 1,000 crore.

From a child who dropped out of school at an early age, Dharampal went on to compete with and outmanoeuvre the highly educated CEOs of many consumer goods multinational companies.

Philanthropy has played a major part in Dharampal’s life for decades, and he supports a large number of schools and hospitals.

Dharampal believes that ultimately man makes his own fate. In his autobiography, he writes, ‘We ourselves are responsible for our victory or defeat, so rather than blaming fate, we should focus on cultivating our strengths and reducing our weaknesses so that this God-given mind and body can be put to full use, so that we know that all our talents and energies are doing

some good in the world.”

****

During the mayhem of the 1947 Partition, lakhs of people lost their homes and livelihoods, while lakhs died. It was a time of catastrophic loss. Despite this, people found the strength to look towards the future and focused on rebuilding their lives and the country they had migrated to. This book captures stories of resilience and sheer grit of people caught in the vortex.

It comprises life stories of twenty-one extraordinary individuals who were deeply affected by the Partition, yet went on to achieve greatness in Independent India. Through their first-hand accounts, they provide a visceral insight into the devastation of families who endured the migration, the camps and the struggle of rebuilding their lives.

Each of these stories is inspirational in a timeless way and the book is ultimately about the resilience and triumph of the human spirit over everything else.

***