The Sublime Music | The Stranger In The Mirror | International Music Day Excerpt

When a movie is sensitive and about to touch a raw nerve, the music has to be very powerful and hold the entire theme together. Fortunately for me, the music of Delhi-6 was created by the living legend A.R. Rahman with additional Ram Leela tracks by Rajat Dholakia (aka Juku). This was my second outing with AR after RDB, which had already been declared a classic. We had an understanding.

I first met AR with Jhamu Sugandh, who had financed a part of my first film Aks and presented both Ashutosh Gowariker’s Lagaan and Mani Ratnam’s Bombay. He took me to meet AR in Chennai. I narrated a story called ‘Samjhauta Express’ to AR; he even did a lovely soundtrack but that wasn’t meant to be. The next time we met was in London, when he was recording for a musical.

The late ’90s saw a shift in Indian sensibilities. A lot of us wanted to take India to the world in whatever we were doing. We weren’t apologetic about Hindi cinema and believed that our stories were powerful and original. In hindsight, this was a defining period for Indian cinema. Yes, western budgets were bigger, but budgets are never an excuse for making bad cinema. AR led the bandwagon of India’s creators who knew that the only way to export your culture is through art and mass media, be it music, literature, sports or, of course, cinema. He shared Indian culture with the world without expressly claiming to do so. AR’s music is fundamentally universal—it cannot be placed within any silo. In that lies his genius. One of the greatest joys of my life has been to be inside the recording studio when AR is creating a song of mine, not because I feel the need to guide but because I enjoy seeing his creative genius at work.

AR understands something very fundamental: there’s only one truth when you’re making a film—that you’re making that one film. Music, editing, cinematography, art direction, wardrobe, lyrics, actors etc. all have to tell that same story. They all have to serve the film and the director’s job is to remind each artist of the one vision that everyone is working towards. In his words, ‘You could write the most interesting piece of music, but it’s of no use if it doesn’t enhance the film.’ This is the key: a song that works in one film or one setting is unique to that. To say that ‘Punjabi remixes are the rage; lets insert one in our film’ is bordering on insanity. The music has to serve the film. The songs are the emotion the characters need to express.

That’s why AR always wants to understand the script deeply. As a creator, everyone associated with the film is walking a tightrope because neither the story, nor the music it commands may be the flavour of the day. In fact, it may be set way in the past or much ahead in the future. But an original creation always commands attention and is quite enough to shine through!

Luckily, I always plan the music of a film even before I start casting. You could say that I start planning the music when I am writing the script. It helps me integrate the songs into the narrative and take the story forward. My role with AR is to transfer my deepest convictions and feelings for the story—why am I making this film, what are my fears my anxieties, my dreams. He hears me out patiently and then interprets it in his own way.

He understands me and I have always been in awe of his unquestionable genius He knows that my songs are not lip-synched like other Indian films and he respects that. I find it difficult to believe in my characters if they break into a song and dance. I have compromised on this stand of mine on two occasions, once in Aks where Raveena plays a singer and is supposed to lip-sync and later in BMB, when the characters allowed it.

After AR set the music, Prasoon Joshi joined in to pen the lyrics and together we created one of most memorable sound track and songs that the Indian film industry has witnessed. To this day, many call it one of AR’s best works. For me, whatever AR creates is magical.

The way AR and I work is that I keep narrating to him and he keeps creating something magical in his head. The essence of Delhi-6 is of the prodigal son who returns home. I told him that we need a whole new rendition for the qawwali, a musical noblesse conferred upon the world by Hazrat Amir Khusrau, composed in the emotional flavour of ‘Mora Piya Ghar Aaya’.

We don’t discuss scenes like ‘this is the situation, boy proposes to the girl’ or such! He knows the entire flow of the film and its ethos and keeps creating. He kept churning melodies for Delhi-6.

On one occasion, late at night (its only late at night with AR), we were both in the zone and I asked him, ‘Why… Why are humans like this … divided by religion when all religions are just a route to realizing your own self?’ Instead of answering me, he composed ‘Rehna Tu’.

He played the tune to me on the continuum, an instrument which sounds like a violin married a piano. The tune captured the need for a secular mindset that respects individuality—‘be yourself just the way you are’—irrespective of cast, creed, religious or racial biases. There was so much pain in the tune, but oddly enough, the melody was about self-acceptance. Back in the hotel room, I broke down.

Prasoon wrote the line ‘Rehna Tu Hai Jaisa Tu’ and we recorded the song. Later, after the song was done, while I was reading Prasoon’s notes I came across a stanza:

Haath thaam chalna ho

To dono ke daaye haath sang kaise

Ek daaya hoga ek baaya hoga

Thaam le haath yeh thaam le

Chalna hai sang, thaam le

Rehna tu

Hai jaisa tu

(It can’t be two right hands that walk side by side. One hand has to be the left hand and the other will be the right hand. You have to let each hand be.)

I was blown away. I asked, ‘Why is this para not in the song?’‘ It is already too long,’ came the reply. ‘No way, this para is the soul,’ I insisted.

We re-recorded the song with the additional stanza. The lyrics crafted by Prasoon were the perfect yin to AR’s yang and took it to the next level.

The one song that I wanted—about home coming—was taking time. There were times when I wondered what I could do to expedite the theme song I wanted. I read the poetry of Rumi to him, which both AR and I share in our own way. But AR will make you see the difference between creation and creativity. He’s pure genius. You have to let him be and let him do his thing; the music just emerges.

I used to land up in Chennai with a one-way ticket, not knowing when I would return. While there, I kept working on my other scripts inspired by the way AR kept working. On another occasion, at 5 a.m., he shook me from the couch where I was sleeping

AR: Mr Mehra!

Me: Hmmm?

AR: I just had a dream about ‘Mora Piya Ghar Aaya’.

Me: Yeah!

AR: Yeah!

We were both excited like toddlers set loose in a toy store. He gave me headphones where he had recorded himself jamming for 35 minutes. I was absolutely bedazzled, in thrall of The Master’s work. That is when I understood that beyond the noise of Bollywood, Hollywood, Mollywood, when I’m with AR, I am in the presence of Mozart, Beethoven, Tansen, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Chopin, Vangelis all at once, to name a few. His music is transcendental.

In the thirty-second minute of the composition, magic happened! Hidden there, was the theme song of Delhi-6: ‘Arziyaan’. It took AR one year to build this masterpiece.

Maula, Maula, Maula mere Maula

Darareein darareein hai maathe pe Maula

Marammat, mukaddar ki kar do Maula, mere Maula.

(The creases of my destiny are embedded on my forehead like worry lines, fix my destiny, O Lord.)

To give this perspective, the Taj Mahal took 17 years to build. So we were lightning quick, I reckon! But my favourite track in Delhi-6 remains the surreal song ‘Dil Gira Dafatan’.

Dil gira kahee par dafatan

Jaane magar ye nayan

Tere khaamosh julfon ke gehraayiya

Hai jaha dil mera

Uljha huwa hai wahin kho gaya

Tu magar hai bekhabar, hai bekhabar

Dil gira kahee par dafatan, kyon gunj rahee hai dhadkan

(My heart has fallen somewhere, all of a sudden, unexpectedly. But these eyes know the depths of your silent locks where my heart is entangled. There itself it, the heart, has got lost. But you are ignorant of it all. Why is the sound of heartbeats echoing?)

This is the heartfelt hark from a reticent boy to the firebrand girl he loves. In order to bring out true emotion, AR believes that a singer must be able to act out the song when he’s belting it out. For ‘Dil Gira Dafatan’, he wanted a blues feel to the music. So he reached out to Ash King, who didn’t know a word of Hindi and had never sung a Hindi song in his life. So while I taught Ash King how to speak Hindi, AR recorded a line a day and finished it over 17 days. That’s the thing with the man; he never tells you how hard he works.

Now, I had this beautiful song the next step was how to film it so I wrote a ‘dream’ sequence for Roshan. One early morning, Roshan wakes up on the terraces of Old Delhi to discover that the Statue of Liberty is standing tall among the skyline of Old Delhi right next to Jama Masjid. The streets are deserted and when he opens the closed gates to another lane, he enters Times Square. All the characters of our story, including the cow giving birth to a calf, are splattered generously over the landscape: his two diverse worlds had merged, quite seamlessly. The symbols now get mixed up as the Ram Leela parade that one would see in Chandni Chowk travels down Times Square led by break dancers. There is Vincent van Gogh painting a portrait of Bittoo (Sonam Kapoor). As he looks for her, Roshan, now aka King Kong or Kaala Bandar of Delhi-6, finds her on top of the Empire State Building. They kiss in his world.

I envisaged Kaala Bandar to be a metaphor about the evil within in the film. I sent the edit to AR and got the best compliment I have ever got. ‘Mr Mehra, you are a genius!’ It was a classic case of Rahman being gracious in praise; it is his talent that’s exemplary.

The second part of the music of Delhi-6 is my dear friend Juku. Delhi-6 features a parallel music track—that of the journey of Lord Rama depicted as folklore and enacted as Ram Leela, the traditional street theatre of our land, and played out in Old Delhi every year in all its grandeur. Juku composed the additional tracks of the Ram Leela scenes for Delhi-6.

Before starting to make movies, I have made over 200 ad films. Many of my relationships are thanks to that decade in advertising. Juku is one of them, whom I met when I walked into Mumbai’s Grand Centre restaurant one evening with Rajiv Kenkre, one of the finest sound engineers India has ever produced. For the uninitiated, sound engineering is a highly technical skill and can make all the difference to how the audience experiences music. Rajiv ushered me to a table where I met Paresh Rawal, Shafi Inamdar and a very jovial gentleman named Rajat Dholakia. With Juku’s absolute command over the minutiae of music, the evening took an unexpected turn. I started to understand his passion for music and the expression of emotion through music.

I will never forget what happened when I first met Juku.

Me: I will give you `1.25 (sawa rupaiyya is auspicious in Indian culture) and am signing you for a film I will make sometime. I don’t know when, but I will make it.

Juku: Anytime! The purity with which you have offered me sawa rupaiyya is evidence enough for me that we will work together on hundreds of projects.

Unknown to me, this gem of a man, an inventive virtuoso with a yen for music, had also taken a liking to me. Juku says,

Before I met Rakeysh, I had composed music for 400 plays for theatre and films like Mirch Masala (1987). But that evening was a date with destiny at Grand Centre Restaurant and Bar. Later, when Rakeysh was contracted for a commercial, Rajiv Kenkre and I worked on the music and that’s how our musical journey together began.

Juku was pure magic. He went on to win National Awards for Dharavi (1992) and Sunday (1993 [best music direction for non-feature film]). I looked out for every possible opportunity to work with him. So after composing music for over a hundred commercials for me, Juku and I built an unbelievable equation. He was to be a guiding force in my life. Juku was the one who scored the music for my first documentary, Mamuli Ram: The Little Big Man.

*

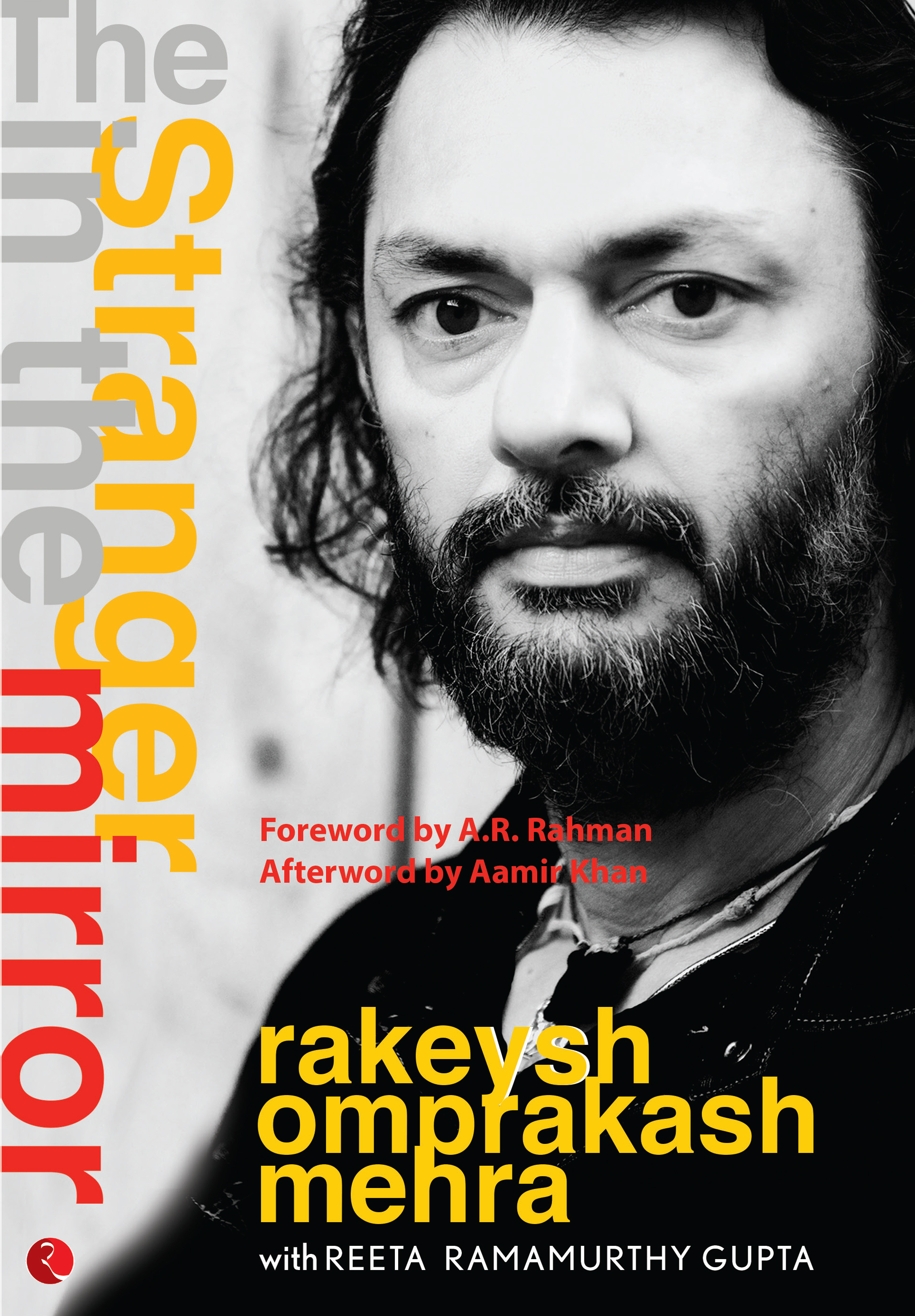

The excerpt is taken from The Stranger in the Mirror

About the Book-

The Stranger in the Mirror is the memoir of the legendary producer-director, Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra. Co-written by noted marketer-author, Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta, this book chronicles the richly experiential, multi-faceted life of one of India’s most celebrated and feted directors who has made critically acclaimed films like Rang De Basanti, Delhi-6 and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag.

Though it may seem natural for an autobiography to have a primary narrator, what makes this book truly unique is its many narrators. It is this multi-dimensional, multi-character narration that will enable readers to delve deep and truly understand what it means to be as unselfish as Mehra, a man who gleefully steps back and lets the experts do their job.

Peppered with anecdotes from Mehra’s life—from the chai-biscuit college days to the popping of the proverbial champagne—it implores readers to pay attention to understand who is narrating, because the plot may have just shifted a little bit, just like his movies. At the end, what really stands out is how effortless the journey has actually been. And herein lies the greatest paradox because there is no lack of perseverance in this journey. The miraculous manner in which things fall into place naturally, like pieces of a pre-ordained puzzle with the universe acting as the ‘sutradhar’, is the fulcrum around which the joy of this remarkable journey is built.