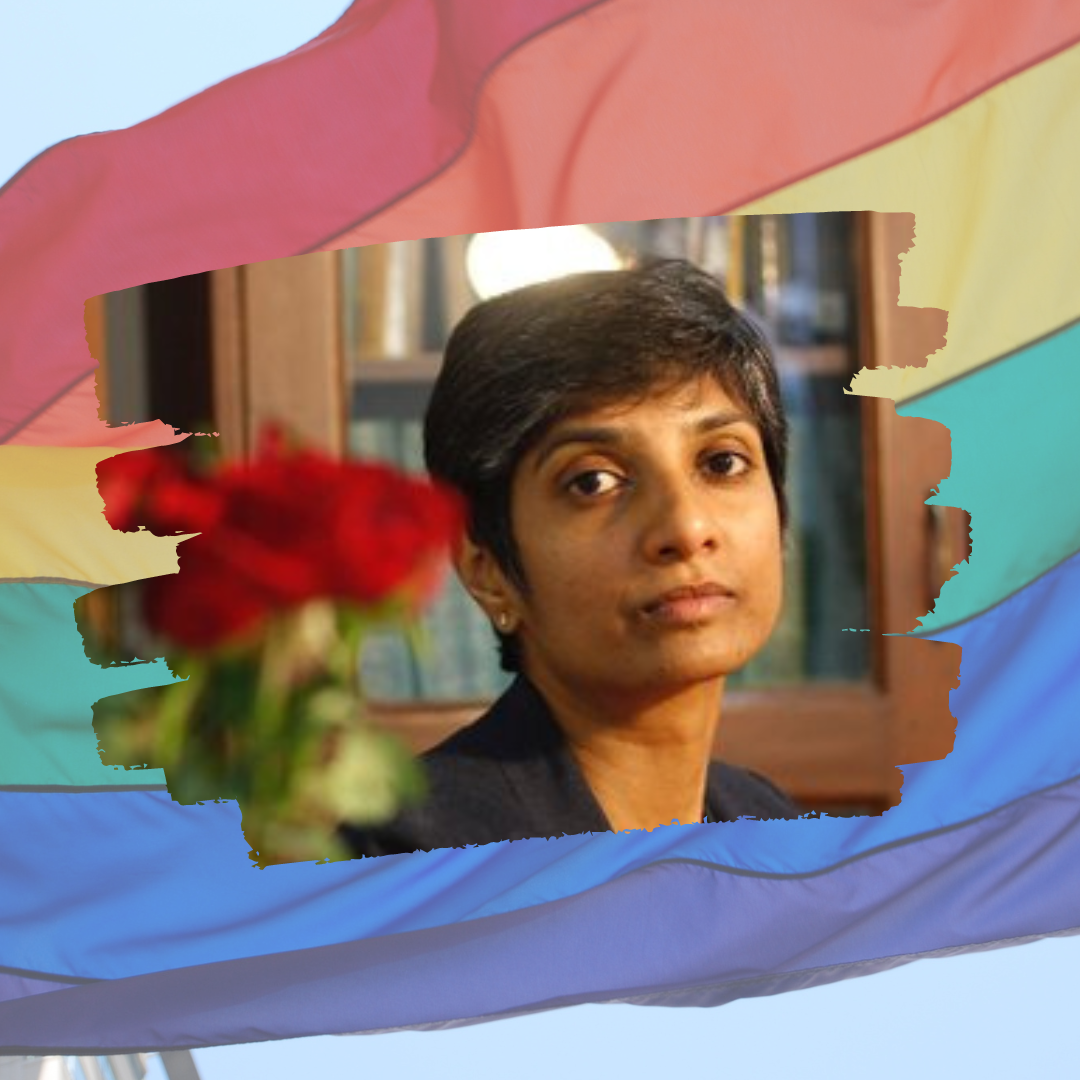

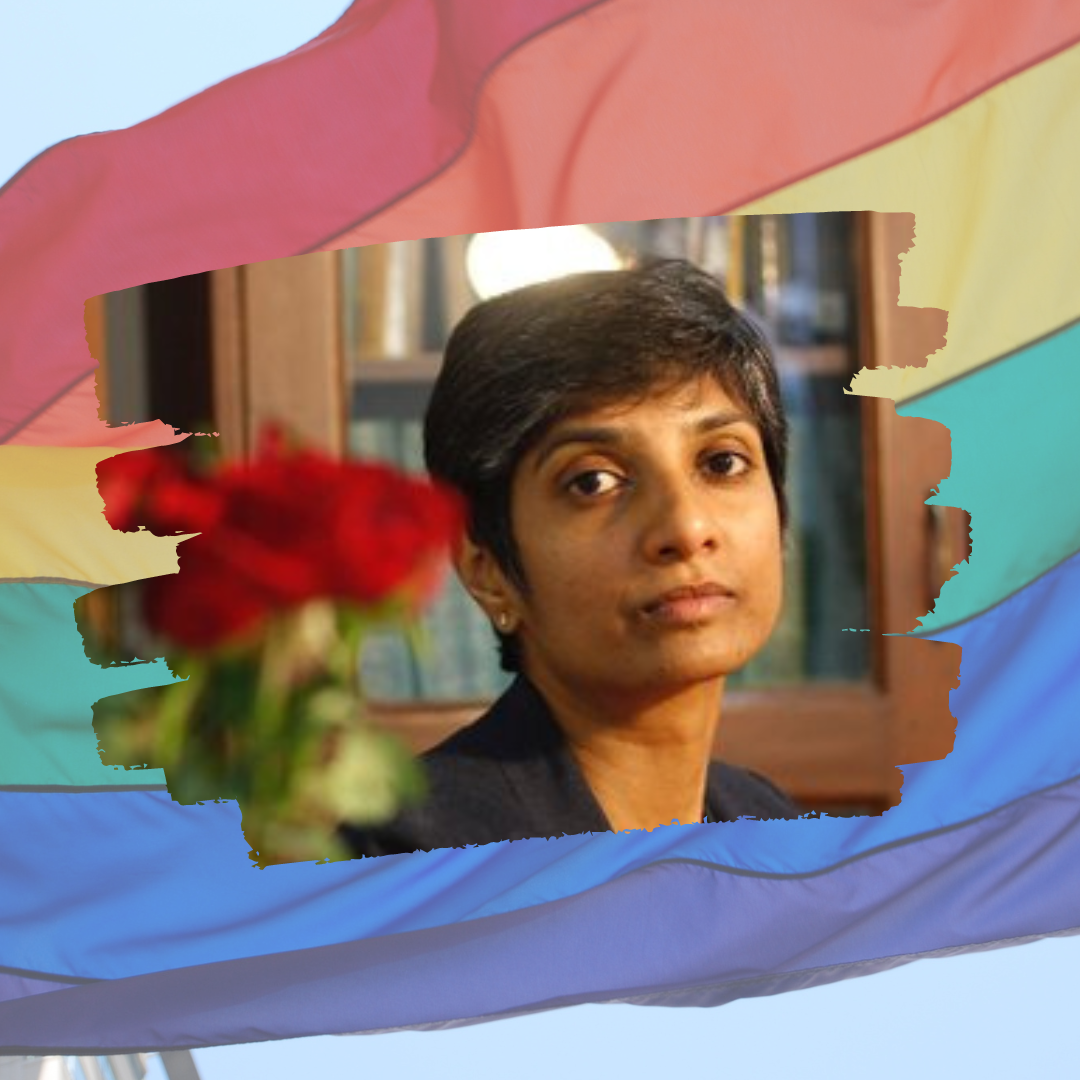

MENAKA GURUSWAMY | The Lawyer who fought the legal battle to decriminalize homosexuality in India

MENAKA GURUSWAMY

The Lawyer who fought the legal battle to decriminalize homosexuality in India

Menaka Guruswamy is imposing in the quiet way that only a woman who is comfortable in her skin is. She can own a room when she walks into it, her gaze is direct, her voice is calm and assured and she is imposing without being overpowering. In her office in New Delhi, the collected works of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar, a recent gift, bears pride of position along with a photograph of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are both men who inspire her, men she admires and whose life work she draws strength from. Perhaps this is also why she is among the top constitutional lawyers in not just the country, but the world over, and why she is so passionate about taking up cases that compel one to revisit the Constitution and defend it. Of all the achievements to her name though, Menaka Guruswamy is most identified with her role in the landmark win striking down Section 377, a win that was historic in the decriminalizing of a colonial era law in India, which considered homosexuality as a criminal act. However, it will be unfair to identify her solely on the basis of this victory.

She bears her many accolades lightly. Senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India, B.R. Ambedkar Research Scholar and Lecturer at Columbia Law School and visiting faculty at Yale Law School, New York University School of Law and University of Toronto School of Law, she has to her credit many other.

landmark cases, including the bureaucratic reforms case, the infamous AgustaWestland case, the Salwa Judum case and the Right to Education legal battle, among others. She’s been amicus curiae with the Supreme Court in the case concerning the alleged extrajudicial killings in Manipur, perhaps the first time that the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) has filed 41 first person reports (FIRs) against security personnel.1Apart from these achievements, she’s worked as an advisor with the United Nations Development Fund and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in New York and South Sudan on international human rights law. She’s worked with Nepal on the constitution-making process.

Her parents, Mohan Guruswamy, a former advisor to the Ministry of Finance, and Meera Guruswamy, an advertising professional, were far removed from the world of law. But her mother was fascinated by it and steered young Menaka towards the world of legal strategy and the words of legal luminaries. It had a profound effect on Menaka. She had her early education at the Hyderabad Public School, completing high school at Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, New Delhi. In 1992, she was all set to take up economics when serendipitously her mother read about the National Law School of India University (NLSIU) which had been set up a few years ago on the outskirts of Bangalore. She recommended Menaka give law school a shot, stay there for a year and see if she liked it; if she didn’t she could always come back to Delhi. Menaka went to NLSIU and loved it.

She found her passion within the Constitution of India and went on to study law further, going on to being awarded the Rhodes Scholarship to read for the Bachelor of Civil Law (BCL) at the University of Oxford in 2000, and the Gammon Fellowship for her Master of Laws (LL.M) at Harvard in 2001. In 2015, she was awarded a DPhil from Oxford for her thesis on constitutionalism in India, Pakistan and Nepal.

She began her professional career in 1997 working with the then Attorney General of India, Ashok Desai, whom she considers a mentor, focusing on litigation and constitutional law. She was just 21 then, the youngest in the office. Everyone around in court were at least twice or thrice her age and women were just about getting into the legal profession. While she was there, she was amongst the juniors on the team who worked on controversial cases like the Jain Hawala case and the fodder scam case, among others.

She went to Oxford a year and a half later to study further. In 2001, after completing her BCL at Oxford, and her LL.M from Harvard, she practised for a while at Davis Polk & Wardwell in New York as an associate. But she came back to India, to New Delhi. Her heart, she says, was in constitutional law, specifically Indian constitutional law and she is most enthused to fight cases around constitutional rights in India. Also, in an interview, she confesses that her favourite thing to do is to walk down the streets of New Delhi in early winter, past heritage structures, with the sun just right—a reminder of what she loves about the country and why she decided to come back home. Her current practice at the Supreme Court of India covers corporate, constitutional as well as criminal law. She has also represented the Union of India, and the National Capital Region.

What really did shoot her into the limelight was her role in the legal battle to decriminalize homosexuality in India. In April 2016, a team of lawyers filed a landmark petition in the Supreme Court, representing five LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) petitioners who were challenging Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 which criminalized homosexuality. Menaka was part of this team, along with Arundhati Katju. The petitioners were led by Navtej Singh Johar. This was the first time ever petitioners had filed in the Supreme Court that Section 377 violated their fundamental rights. Menaka appeared for these petitioners and also for subsequent petitioners who were tudents and alumni of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) from all over India.

The judgement by the Supreme Court reading down Section 377 as not applicable for consenting adults, was a landmark one, leading to much celebration amongst the LGBTQ community in India, who were finally now, free to love. After the historic verdict decriminalizing Section 377, Menaka and Arundhati announced on the Fareed Zakaria talk show on CNN that they were in a relationship and this coming out of the duo who had worked on this case created ripples, with their victory in this case now just not only a professional one, but also one that was a huge personal vindication. On the show, she told Zakaria about the sinking moment during the earlier hearing of the case in 2013 when she realized that the verdict would not be in their favour. A senior judge asked a law officer if he personally knew any homosexuals, to which the officer laughed, saying he was not that modern. In that instant, Menaka realized that the judge did not even realize what the concept of being gay in India meant, when she was standing right there, before the Bench. That moment of invisibility to her was the erasure of what she and so many other LGBTQ Indians faced. The battle was personal; decriminalizing Section 377 was reclaiming the rights of so many like her who were denied being equal citizens of the country, thanks to an antiquated colonial era law. In her arguments, she would tell a five-judge Bench, ‘How strongly must we love knowing we are unconvicted felons under Section 377? My Lords, this is love that must be constitutionally recognised, and not just sexual acts.’

Among the other high-profile cases that she has been part of are the Salwa Judum case and of Nandini Sundar versus the State of Chhattisgarh in 2011 which was about the existent practice of using tribal youths to fight against Maoist insurgency and led to the disarming of the youth. The next year, she was appointed amicus curiae in the case of the alleged 1,528 extrajudicial killings by the armed forces in Manipur. She proposed the setting up of a Special Investigation Team to look into the killings. She represented former Air Chief Marshal S.P. Tyagi before a special CBI court in the AgustaWestland case, a case that had created headlines because of the kickback allegations in a helicopter purchase deal.

In 2019, she was made senior advocate by the Supreme Court of India. Among the many honours she has received, the portrait of her hung at the Milner Hall in Rhodes House at the University of Oxford, is among the most poignant, making her the first Indian and only the second woman ever to receive this honour. She is nostalgic about what it means for a brown person, a woman, who remembers coming to Oxford and seeing only portraits of white men hung in those hallowed halls, to now see her own portrait adorning them. In her acceptance speech, she spoke about what it meant to be a woman from India coming to receive this honour, the awareness of the exploitative colonial legacy that the Rhodes Scholarship was built upon and how future Rhodes scholars had the responsibility to re-imagine the scholarship and to use the legacy to enhance equality and disseminate opportunities. To quote from her acceptance speech, As an Indian, it was even more poignant to come for a post-graduate degree in England, whose history of colonisation and plunder of my country is something we still pay for. And whose lingering colonial remnants include poverty and deep divisions that have not healed.How it is then that one reconciles moral integrity with the enjoyment of such privilege that the Rhodes Scholarships and an Oxford degree bring? One does so by deploying this privilege to good use: by that, I mean to push the envelope in ways that this privilege allows you to. To ask tougher questions of authority, to attempt to always expand human freedom and be aware when our footsteps contract such freedom, and to practise our professions in ways that better perpetuate equality, and never to forget that our higher education degrees, our time in this Oxford sunshine and the ability of this extraordinary scholarship to open doors is built on the backs of Africans.

Also in 2019, she was in Foreign Policy’s 100 Global Thinkers List, with other names such as Michelle Obama, Kofi Annan and Jeff Bezos, amongst others. The same year, Harvard Law School included her in a portrait exhibition of Women Inspiring Change and she was among Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People. Forbes India included her in their 2019 list of Women Power Trailblazer. She also has a number of essays in various publications to her credit and has co-edited Founding Moments in Constitutionalism published by Hart/Bloomsbury, UK.

She is also working on a book on South Asian Constitutionalism, apart from which she writes extensively for publications like The New York Times, The Hindu, The Indian Express and Scroll, to name a few. If she didn’t become a lawyer, she thinks, she would have become a professional chess player; she jokes that one of her childhood aspirations was to become a backup dancer to Madonna, but that her cousins dissuaded her, telling her rather bluntly that she didn’t have the talent for it. Chess, her other passion, has a lot in common with law, she feels; one must strategize, see the entire board, anticipate the opponent’s moves. Litigation and law were her second option, something she had been fascinated with from an early age. Among her icons, she counts Cornelia Sorabjee, who was the first Indian woman to become a lawyer at a time when only men were admitted to the bar. She was also the first woman to read law at Oxford and Guruswamy sees her as a role model, as someone who set the path that she has now, years later, followed.

Travel is a passion and she’s been lucky to have her work take her to different parts of the world as well: Nepal, South Sudan and New York, to name a few. Her favourite book, if you ask her, is something that is definitely not light reading: the Constitution of India. She holds it in high regard, so much so that she chooses to focus on constitutional law. And she continues the battle for the LGBTQIA community, now with her battle to legitimize same-sex marriage in India. As she says, it is a long journey, there’s a lot to be done. And she is only just getting started.

Excerpts from a conversation with her: Growing up, what made you take up law as your chosen career given that in India the tide is generally focused towards medicine or engineering? Was there a turning point or an incident that made you take this decision? In fact, it was my mother who was super enthusiastic about me becoming a lawyer. My parents were not lawyers. My mother is a copywriter and my father was an economist. She would show me clippings of articles by eminent lawyers like Ram Jethmalani to get me interested in the field. In school, I did participate in many elocution competitions, debates and recitation competitions, and therefore I became comfortable thinking about ideas, with speaking in public, and I thought this is a good career option to pursue. For girls in India, to have supportive parents is a very important thing. We are still very much a patriarchal society, even more so back then. I am 45 now, I went to law school when I was 17, that’s over two and a half decades ago. At that time, this law school had just been set up and no batch had graduated yet. It was a big thing to take that call to opt for the five-year law course. I had finished my schooling in Delhi, and had already applied for colleges here. I’d gotten into LSR [Lady Shri Ram] and St Stephen’s. It was a risk of sorts I was taking, because at that point, law was traditionally taken up after getting your first degree. The five-year law degree is a recent phenomenon in the last 15 to 20 years. Traditionally law would be a second degree and one went to law school after graduating. But, both my parents have always been so incredibly supportive. I think I fell in love with law at law school, I think it took them by surprise as well about how deeply passionate I was, and am about it. You said in an earlier interview, you found an approach to teaching law at the National Law School of India University that has been lost.

Could you tell us more about your experience as a student there, and how it influenced your career trajectory? We were the fifth batch at NLS.

When I was in the first year, the fifth year hadn’t graduated yet. It was an interesting experience, for one it was far removed from the big cities at the time. It was an idea of a few people to have this kind of a five-year programme, it brought back the integrity of the exam system. You had to attend class. I’d get into trouble for not attending class. Being so far from city life, it gave you the time and space to grow into yourself. You had students from all over the country, you made friends across the board. There’s something so wonderful about an educational institution that attracts students from all over, you have different educational backgrounds, different cultures, different ethnicities, different religions, and it really taught you about the diversity of the country.

How has this experience at the NLSIU influenced, if at all, your approach to teaching now, as a professor?

I’ve been to different institutions now since I have a PhD from Oxford. When I joined the National Law School, it was a struggle to stay afloat. I learnt from that struggle, that you pick your own path and often those paths are not easy ones. I learnt this from the institution, from the man who founded it, Madhava Menon, from what a battle it was for him to find land, to find an uninterfering government, to build an institution on merit and to build an institution that said that the law must care about what is happening in the country. Also, by studying abroad you expand your world. You see different legal systems. It teaches you to compare and contrast. Being away from your country gives you time to reflect, and when you go to institutions that are serious about what they teach, they also give you the opportunity to interact with good teachers, motivated teachers, teachers who are generous with the time they give you, the ideas they are willing to discuss with you, it makes all the difference to your own approach.

You have a special interest in constitutional law. What is it about constitutional law that appeals to you?

The constitution of any country is part law and part politics. It is a text made by history and politics. It does two things: one, it tells you what your country is meant to be, what your country must aspire to and two, it is a very important way, when you litigate constitutional law cases, of expanding freedoms. I have a general practice, I do everything from criminal to corporate to constitutional law. I really enjoy doing criminal and constitutional law. Constitutional law is important for exactly this, that you can litigate things for the idea of your country, for those whose freedoms are being compressed, and makes you aware about why it is important to fight for these. You have, in your legal career, taken up a wide variety of cases. What is it about a case that makes you decide to take it up? Why to take a case is a decision you make on a daily basis. New cases come in, solicitors bring in new cases, so forth. I take cases that are interesting in criminal and commercial matters. I like representing all kinds of people, corporates, those accused of crimes, as well as those from the most vulnerable sections of society. What makes my job interesting as a lawyer is that you get to meet and interact with an array of people, you learn not to prejudge very quickly, you learn to understand the whole range of what actually motivates human beings. This idea that the guilty mustn’t be represented is something I strongly disagree with. As lawyers, we are expected to take up all kinds of cases, we may be more motivated to take certain kinds of cases. In my case, these are cases about freedoms, about an unaccountable state, cases about the right to life. But equally so I find it interesting to represent corporations, to do bankruptcy cases, tax matters, and in the early years of my career, I represented the government and I would prosecute crime. If you practise in Delhi, in the Supreme Court, there is a great joy in getting that array of cases. Also, as a lawyer, you have to read up for your cases, you have to keep reading new things so there is a constant learning that is part of the job. There is something so cerebral and so intellectually satisfying about it. I may sometimes get very excited about some technicality in regulatory laws in a case that has come to me, and I’m very happy to do it, but at the same time, I’m equally happy to do a large rights case where the state has been accused of being unaccountable.

As kids we used to play with the Rubik’s cube. I found it fascinating because you had to get a combination of things right. A case is just like that; you have a statute, you have an opposing party, you have a law that has been set or perhaps a law that needs to be overturned, all the things need to be set correctly for everything to fall in place. Two things I really love: Rubik’s cube and chess. I played chess very seriously when I was younger and litigation is a lot like chess; you have to strategize, you have to think ahead, you have to know what combination will get you ahead. You have to think of all the pieces on the board, the opposing side’s pieces and moves, as well as your own pieces.

You are the first Indian and second woman to have her portrait hung at the Milner Hall in Rhodes House at the University of Oxford. What was your reaction when you heard of this honour, and why do you think it is important to have visible icons across gender, race and orientation in spaces like these in academia?

It was quite surprising. They just send you an email saying this has happened and we’d like to have your portrait painted, and so at first I thought it was a joke. I was travelling for work, so I just ignored the email. After a week I got another message from Rhodes House saying, ‘Excuse me, did you get our previous email?’ And that’s when I realized that this was genuine. When the portrait was unveiled and we had a small ceremony, I did say this at the time, that the legacy of Cecil Rhodes is a pretty dark legacy, it is the legacy of colonisers. The Rhodes scholarship is basically built on the backs of Africans, because Rhodes made his fortune from Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe and the surrounding areas. So in some way, the origin of these scholarships is very dark. So getting these scholarships, it gives you enormous privilege, but the point is—what do you do with this privilege, how do you deploy it? How do you deploy these little platforms of privilege? For me, it was very important to have these difficult conversations, to do the hard cases, to write the hard pieces and to keep pushing. When I went as a young person to Oxford, I was 21 and as I looked around me at the walls of the universities, I saw only white people, only white men. I remember in the orientation programme, the Master of Ceremonies kept calling out the countries the students were from, he went through a list of North American and European countries and left out all of the Global South. The fact is that these institutions have to change, they have to be held accountable and we are part of the process of making that change. Former alumni like me are part of the process of engaging with the institution and making change possible. One small part of that change is about what is hanging on their walls, and another part of that change is who is hanging on those walls and what are they doing about their lives. There are stories there. I hope the young students of colour who go to Oxford now and see these other portraits that have been recently hung, will feel that places are more accessible to them, more friendly to them, that their stories are possible, that they are going to have wonderful lives ahead, where they have the opportunity to do meaningful work, interesting work.

The verdict that struck down Section 377 was a landmark verdict and a long, hard battle that you fought along with the others in the team.Tell us about the moments of despair and struggle when you perhaps were disheartened, and the little moments in the years that it took for the case that kept you going.

It has been a 20-year battle. We got involved a little after 2010, when appeals were filed against the judgement of the Delhi High Court. While it’s been a long battle, what were the choices? I’m a queer person who is a lawyer. When we lost this case in 2013, I felt anger. I am not an angry person. But in 2013 to be called a criminal by your own workspace, it left me hugely angry. My instinctive response to this is that this is not okay. What are we going to do about this? What can we do differently? I am not made in that way, I don’t know how to walk away. The biggest relief that one gets when a case ends is that the anger ebbs, because anger is not really a productive emotion. I had a wonderful teacher and mentor, and a senior, Ashok Desai, who was an attorney general. I interned with him while I was at law school and then after I graduated from NLS. He passed away in March 2020. He was Buddhist, and he taught me about being detached and keeping anger at bay. He had been part of this case from 2008, I had taken a brief to him, and so, in a sense we lost together. He called me the next morning after the verdict in 2013 saying, ‘Okay, so what are we doing to overturn this?’ It meant the world to me that my mentor who was senior counsel, former attorney general, was equally pissed off. I think when you come from that kind of office, with those kind of teachers, it is very difficult to give up. You don’t have the skill set to give up. I’ve made peace with the fact that we will win and lose a lot of battles. And a big thing for young people to consider is in life you will have happiness and disappointment, personally and professionally, that loss will teach you far more than success ever will; the best thing to do is to not get disheartened and keep going on to make things right.

What are the good things you have in your life?

For me, I have a wonderful family and a wonderful partner, friends and colleagues, a skill set and an occupation that gave me joy. I believe in counting my blessings at times like this. I would say, pick very carefully what you choose to do with your life, your career. That will make all the difference.Having now won this battle, you are moving on to push for legislation to allow same-sex marriage. It’s a process, we will do anti-discrimination, the transgender act needs to be contested, before we get to same sex marriage. It is a journey. There’s a lot to be done. Gay people all over the country just want to lead full lives, and we must do what we can.

Who are your icons? What inspires you about them and their work?

It might seem odd to say this in 2020, but professionally and personally for me, two very big heroes are Bhimrao Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru. They were both lawyers, both picked very different paths. Ambedkar’s life meant so much. An untouchable, sitting at the back of the class, not allowed to drink water from the same pot. Knowing and reading about his life, his quest for learning made me realize that knowledge is important, and how his quest for knowledge culminated in our Constitution. I just received a gift from a young solicitor of the collected works of Ambedkar, and I have it in my office, as well as a picture of Nehru and they’re both very inspiring. Nehru, the son of the richest lawyer in Allahabad, educated abroad, chooses to give it all up for the freedom struggle, goes to prison for cumulatively nine years, spends his time in prison writing his books. The Discovery of India ends abruptly, because he runs out of ink and paper and they don’t give him more. They’re both human beings who’ve had hard, difficult and meaningful professional lives and there’s so much to learn from their journeys.

Time magazine named you and Arundhati Katju in their list of 100 most influential people of 2019. What would be the ultimate honour that you still hope to achieve? What is the fight you still must fight?

I’m just getting started, honestly. I’m 45 now, I hope to have 25 to 30 years of professional life ahead of me, and I have an enormous amount of work to be done. For me, it is really the small joy of winning a case, and looking at the family’s face when a loved one is out of prison, or when a loved one has been killed and justice has been delivered. It is those moments that make it all worthwhile.

Coming out on the Fareed Zakaria show was something that was an act of bravery and also an act of solidarity with the community you fought for so long and hard. What was the response to it, and how liberating was the feeling to finally come out to the world?

It wasn’t like our colleagues or our neighbours or our families didn’t know that we were partners. People knew. But for me, it boiled down to the conversations when I was growing up, when I was a young law student and I did not know if it was possible for a gay person to be a successful lawyer, I did not know if we could have happy lives. I would like young gay people to know that you will have happy and healthy lives, in as much as it is hard to be a young gay person, I think going through that process will get you to a place of personal happiness. I’d like them to know that they will have an array of role models who will be honest about their sexuality which is what will help young people to have happier lives, less mental health issues. Not just for queer people, but also when it comes to caste and religion, it is so importantto have these pictures of strength across the board.

Why is Ambedkar so important to all of us, and not just to Dalit Indians? It is because he told us through his life that your dreams are possible.

I hope in 20 years we have young queer kids in India growing up with fewer challenges than my generation did, that would be true success for us. That’s what it is all about.

Excerpted from RISING 30 WOMEN WHO CHANGED INDIA By Kiran Manral