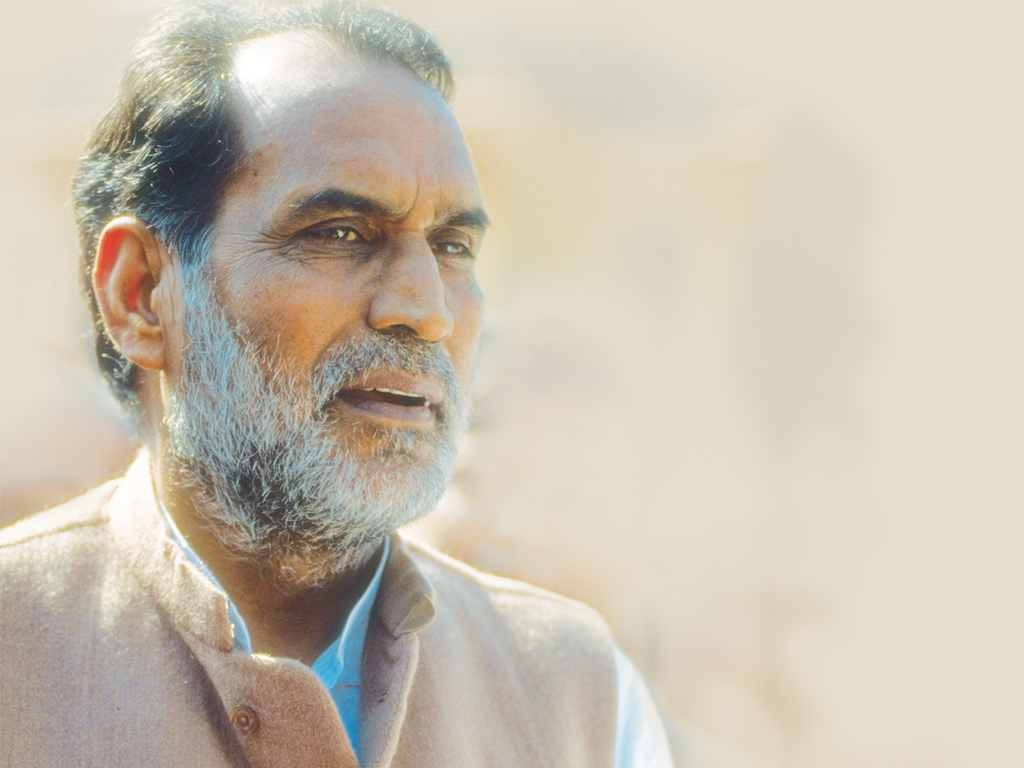

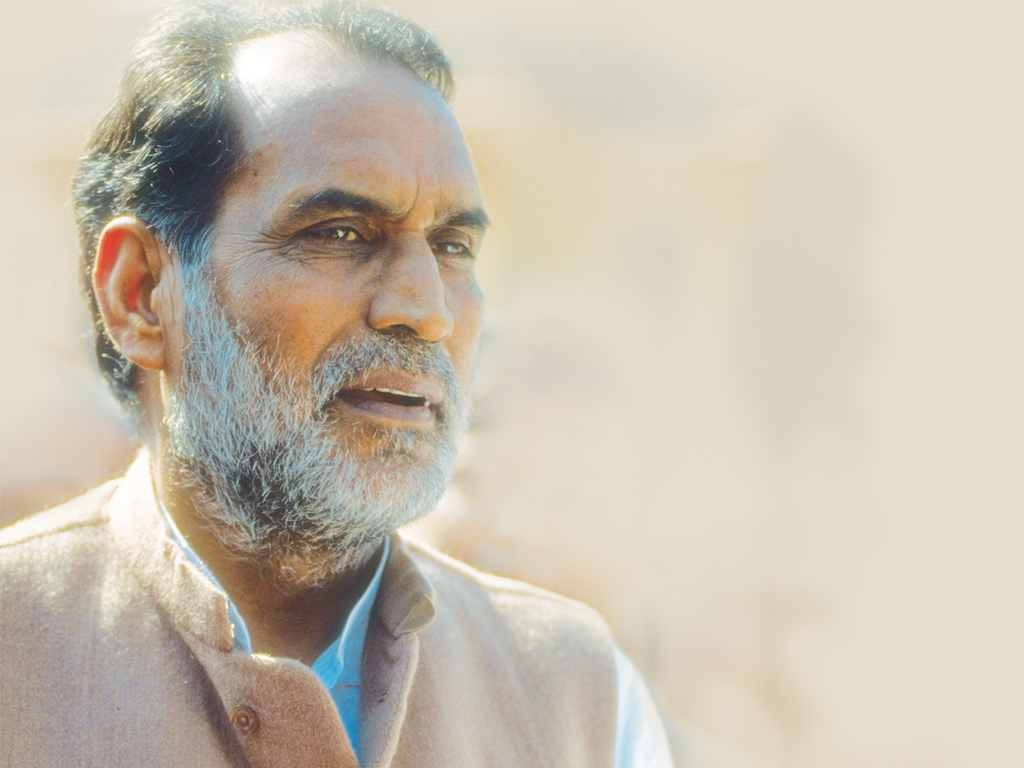

Chandra Shekhar – The Last Icon Of Ideological Politics

In 1963, Ashok Mehta, the veteran leader of Praja Socialist Party (PSP), proposed his theory, ‘Compulsions of the Backward Economy’. He recommended that in developing nations, the Opposition parties should collaborate with the government on critical issues to achieve rapid development. Mehta encouraged Indian socialists to extend cooperation to the Congress government. Jawaharlal Nehru then invited him to assume the deputy chairmanship of the Planning Commission. Consequently, the inflexible socialists expelled Mehta from the party. One man from PSP, also a member of the Rajya Sabha (House of Elders) then, publicly opposed his expulsion, going against the decision of his own party colleagues. That lone crusader was none other than Chandra Shekhar, who was expelled from PSP after this incident. He remained an unattached member for six months before eventually joining the Congress.

As a young first-time parliamentarian, Chandra Shekhar had already carved a niche for himself in the Rajya Sabha, and was known as an accomplished orator, ideological aficionado and uncompromising activist-politician. Some cerebral politicians such as Gurupadaswamy, Inder Kumar Gujral and Ashok Mehta used to meet Indira Gandhi every evening for wide-ranging discussions. Most of them knew Chandra Shekhar and they would insist that he too should come along to these informal chats. Initially, Chandra Shekhar was quite reluctant to join these get-togethers; however, upon repeated requests from his friends, he went to see Indira Gandhi one evening. All of them, including the regular visitors, were sitting outside in the lawn. Below is probably the first casual conversation between Chandra Shekhar and Indira Gandhi and it reveals a lot about his frank and forthright approach to politics:

Indira Gandhi: Do you consider Congress party a socialist unit?

Chandra Shekhar: No, I do not believe that Congress is a socialist organization, though some people believe so.

Indira Gandhi: Then, why did you join the Congress?

Chandra Shekhar: Do you wish to know the truth?

Indira Gandhi: Indeed, I do.

Chandra Shekhar: I dedicated thirteen years of my life to the PSP and worked with all my capabilities and honesty. I tried my best to steer the party towards the socialist path. However, after working for a long time with the party, I realized that its organization was in disarray and the party itself was disoriented. It dawned on me that nothing substantial can be achieved in this scenario and, considering Congress to be a major political force, I decided to join the party and work for those objectives.Indira Gandhi: What would you like to do now that you are here?

Chandra Shekhar: I would like to steer the Congress party towards true socialism.

Indira Gandhi: And if you don’t succeed?

Chandra Shekhar: I will endeavour to break the party, for I believe that unless Congress is fragmented, no new kind of politics can emerge in this country. My first effort would be to bring socialism to the party but if I fail, there will be no option left other than to ensure its disintegration.

Indira Gandhi: I am simply asking you certain questions and this is how you respond to me?

Chandra Shekhar: If you are asking me questions, my answers will be directed to you.

Indira Gandhi: What do you mean by breaking the party? What can be achieved by this?

Chandra Shekhar: Congress has morphed into a big banyan tree and no other plant can grow under its shadows, therefore, unless this party is fragmented, no revolutionary change can be forthcoming.

Chandra Shekhar later recalled that at the end of the conversation, Indira Gandhi was looking at him in utter astonishment. This was the very first informal chat between Indira Gandhi, the daughter of Prime Minister Nehru, the elite among the elites, and Chandra Shekhar, the subaltern among subalterns.

This is the story of an ordinary man who did not inherit a grand legacy from a well-established and renowned family, who did not rely on family wealth and eminence, who did not attend any of the prestigious educational institutions in the country or abroad, and who did not command a dedicated vote bank of a specific class, caste or community. He took on the most powerful prime minister of her time and became a formidable opponent of her politics and policies. It is the story of a man who hailed from a poor rural background and who, despite stiff opposition from Indira Gandhi, won the nomination to the Congress Working Committee (CWC)—not once but thrice. Chandra Shekhar was the only person other than Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to be elected to the CWC despite the disapproval of the party’s top leadership; consequently, several of the Congress members started to refer to him as Netaji Subhas.

As mentioned earlier, there are only three instances in independent India, when someone from humble origins rose to occupy the chair of the prime minister of India. On Chandra Shekhar’s appointment as the prime minister of India, his long-time friend, a prominent Hindi littérateur and parliamentarian, Shankar Dayal Singh, wrote about the many odds Chandra Shekhar had to overcome to become the prime minister. Singh wrote that Chandra Shekhar was an incredibly fortunate man to rise as far as he did because he did not have the handsome face of Rajiv Gandhi, did not hold the title of ‘Raja’ of Vishwanath Pratap Singh, did not possess the dedicated community support of Choudhary Charan Singh, did not inherit the family legacy of Indira Gandhi, did not enjoy the starched whitewashed crisp reputation of Morarji Desai, and did not wear the timid vulnerability of Lal Bahadur Shastri. Chandra Shekhar’s political journey was perhaps not ‘destined’, but his devotion to socio-economic issues and exceptional personal characteristics distinguished him from his contemporaries.

Chandra Shekhar was born on 17 April 1927 and left this world at the age of eighty on 7 July 2007. He was active in Indian politics at a time when both idealism and ideology were cherished, and ideological conviction was treasured. It is arguable that Indian politics abandoned its lofty ideals and ideological commitments during Chandra Shekhar’s lifetime itself and he witnessed it as both a mainstream player and a bystander. Chandra Shekhar was greatly influenced by Acharya Narendra Dev and was a worthy inheritor of his legacy. Acharyaji was recognized as the most learned exponent of Marxism in India, an authority on Buddhism and an exceptional scholar of Tantra. Jawaharlal Nehru referred to Acharyaji as one of the two living encyclopaedias, the other being Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. Chandra Shekhar always believed that no matter how hard he tried he could never become like Acharya Narendra Dev.

The year 1955 witnessed the split of the PSP; on the one hand was the irascible, flamboyant and adventurous Ram Manohar Lohia, and on the other, the humble savant-like and temperate Acharya Narendra Dev. Chandra Shekhar chose to follow Acharyaji.

Chandra Shekhar had a keen sense of conduct, etiquette and decency. He was extremely courteous to his seniors, colleagues, associates and juniors. He believed in utmost civility, genuine equality and inviolable dignity in his interpersonal interactions. His sense of self-respect prevented him from behaving like a feudal landlord with others, no matter how ordinary a person was. At the same time, it did not let him endure any arrogance from others, no matter how big the person was. One of his associates, Uday Narayanji, described an incident that provides an insight into Chandra Shekhar’s values. Once Chandra Shekhar was travelling by train to Varanasi and asked Uday Narayan to arrive at the Sarnath Guest House with Bihari food such as baati chokha and daal chawal to feed around eight to ten people. A man named Saryu was the attendant at the guest house. Upon reaching the guest house, Chandra Shekhar instructed his associates in Bhojpuri, ‘Pahile Saryu ke khana lagaa da log. O khojat hoee ki sahib aaj aaiyhan ta badhiya khaaye ke mili. Pahile okra ke de da tab hamanee ke khaayal jaaee. (Please serve Saryu first; he must be expecting delicious food on my visit. We shall eat but only after he has had his food.)’

Once, Chandra Shekhar wished to invite Acharyaji to a function in Ballia, however, due to his ill health, Acharya advised him to invite Dr Lohia instead. Lohia agreed to grace Ballia on the condition that he would get a jeep to ferry him out of Ballia to Buxar so that he could catch his train to Calcutta (now Kolkata) on time. As per schedule, Chandra Shekhar went to receive Dr Lohia in a car at Ballia station only to find that the narrow gauge train was delayed. Eventually, his guest arrived, but he looked quite upset. Lohia demanded to see the jeep that would take him to Buxar, and Chandra Shekhar had to explain to Lohia that they would only need the jeep in the evening. Lohia lost his temper and started scolding Chandra Shekhar, accusing him of lying and misleading him into visiting the place. Initially, Chandra Shekhar ignored Lohia’s accusations; however, Lohia continued to accuse Chandra Shekhar of deception and trickery. Ultimately, an incensed Chandra Shekhar replied rather tersely, ‘Dr Lohia, you are not the only one who is honesty personified. In the first place, I did not invite you; it was Acharya whom I had invited and you have come here on his request. Please leave us with our dignity. I thank you for your visit, but you may leave.’

This episode is important because, in 1952, Dr Lohia was at the peak of his popularity and influence in the socialist movement while Chandra Shekhar was unknown—a petty functionary of the party. Later, he recollected this incident and said, ‘Even to this date, I am astonished that as a young man then I could speak to one of our senior-most leaders in that manner. Maybe I could not help myself as I was furious at being called a liar.’

There were numerous occasions when Chandra Shekhar chose to take on the powers that be and suffered severe consequences. He never allowed any sense of real or perceived outrage to blind his idea of fairness and courtesy. In 1977, when he learnt of Morarji Desai’s plan to evict Indira Gandhi from her government bungalow, he challenged Desai to rise above his pettiness. Chandra Shekhar questioned the rationality behind denying a small bungalow to a woman whose family had donated Swaraj Bhawan and Anand Bhawan to the nation and who had been the prime minister for eleven years. Eventually, Morarji retreated and let Indira Gandhi stay in her house.

Chandra Shekhar lost the 1984 general elections held after the tragic assassination of Indira Gandhi. The Congress party, under the corporate style management of Arun Nehru, had given him the epithet of ‘Bhindranwale of Ballia’ for his opposition to the military operations in the Golden Temple complex. In the 1989 general elections, his local supporters implored him to change his stance on Operation Blue Star in order to win the elections. To calm his distraught supporters, Chandra Shekhar decided to not argue with them and it was considered that he had indeed conceded to his supporters. However, in the very first public meeting, he declared that his opposition to Operation Blue Star was still as intense as it had ever been. He then asked those people who considered his stand on Punjab a mistake not to vote for him.

This and other incidents demonstrate that Chandra Shekhar was not someone to capitulate in the face of adversity, potential emotional blackmail or the tantrums of the high and mighty. On 25 June 1975, Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency and Chandra Shekhar was arrested on the same night. He was kept in solitary confinement until January 1977. In the middle of December 1976, when it seemed like the Emergency would continue forever, a very senior Congress leader visited Chandra Shekhar as Indira Gandhi’s emissary in Patiala Jail. The emissary told him about Indira Gandhi’s growing frustration with the communists and that she required Chandra Shekhar’s help to launch a new campaign. Chandra Shekhar explained that even though he had political differences with the communists, he was not anti-communist and that he could not be of any help to Indira Gandhi. When the emissary inquired how long he planned to be in prison, Chandra Shekhar replied that the last eighteen months of solitary confinement had strengthened his resolve and he was prepared to spend the rest of his life as a prisoner. Indira Gandhi’s emissary returned empty-handed, but it is interesting to note that Chandra Shekhar never broached this subject with the emissary after his release and, more significantly, he never revealed the emissary’s identity.

In November 1990, as India was facing several domestic and international challenges, Chandra Shekhar formed a minority government with the support of the Congress party and the survival of this cabinet solely depended on Rajiv Gandhi’s pleasure. In a couple of months, Congress discovered that Chandra Shekhar was turning out to be an acclaimed administrator, admired statesman and, more worryingly, what Financial Times, London, called, ‘an uncomfortably successful prime minister’. The Congress members claimed that Rajiv Gandhi had been spied on and blamed that somehow the prime minister was responsible for placing two Haryana police constables outside Rajiv’s home. Chandra Shekhar was deeply disappointed with Rajiv’s imprudence and sent his resignation to then president, R. Venkataraman. Rajiv Gandhi had not bargained for this and sent Sharad Pawar with a message requesting Chandra Shekhar to withdraw his resignation. Chandra Shekhar’s response to this is illustrative of his personality and leadership, ‘Go back and tell him that Chandra Shekhar does not change his mind three times a day. I am not the one to stick to power at any cost. Once I decide on something, I carry it out.’

In the aftermath of Rajiv Gandhi’s sad demise in 1991, his family wished to construct a memorial for him by dividing Lal Bahadur Shastri’s memorial. But Chandra Shekhar wanted to allocate space within Indira Gandhi’s memorial at Shakti Sthal instead. It was a night-long high-profile drama that involved tantrums from Gandhi’s family. Narrating this incident, Subramanian Swamy wrote that despite the melodrama, Chandra Shekhar did not agree to the partitioning of Shastri’s memorial.

It was interesting to note that Sonia Gandhi did not want Rajiv’s memorial to be housed within Indira Gandhi’s memorial. This was because Sonia wanted a dedicated location for Rajiv Gandhi to portray that he was a leader in his own right and not just Indira’s son. Chandra Shekhar argued that Shastri, a freedom fighter, a self-made politician and an elected prime minister was a great leader of the masses. Chandra Shekhar ensured that Shastri—the first ordinary person to be an extraordinary prime minister—was given due reverence and his memory was honoured.

Chandra Shekhar played a historical role in Indian politics as a ‘Young Turk’. Prof J.C. Johari described him as a ‘member of the Rajya Sabha—the prince of the Young Turk community’. He was at the forefront of the campaign for bank nationalization, abolition of privy purses and implementation of the election manifesto. He could challenge Indira Gandhi for not fulfilling her election promises and could even win the election to the Congress Working Committee, against her wishes. In the midst of growing distrust between veteran leader Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Chandra Shekhar was the only one who could publicly advise Indira Gandhi to seek rapprochement with JP.

During the times when ‘Indira is India’ was the only mantra of pliant Congressmen, Chandra Shekhar invited JP for a tea party at his home—an informal gathering—that attracted over sixty parliamentarians from the Congress party. As a result, in the Congress party’s Narora camp, which followed this tea party, the people spent both days of its session discussing Chandra Shekhar’s tea party. I.K Gujral wrote in his autobiography that it appeared that the Narora camp, organized to censure Chandra Shekhar, actually ended up raising his stature in the party. However, the declaration of Emergency saw Chandra Shekhar—the face of intra-party opposition to the dictatorial Indira and Sanjay Gandhi—not just behind bars but in solitary confinement.

Chandra Shekhar played a critical role in several major events that shaped Indian politics between 1950 and 2007. But he remained grounded and was not averse to swimming against the tide. He emerged as an effective alternative to the Nehru-Gandhi family for the Congress party’s leadership, and his expulsion from the party was the beginning of the end of Congress as a political force. It sent a clear message to everyone that the Congress party would not endure any powerful and popular leader who was outside the Nehru-Gandhi family circle. Ironically, once upon a time, the same Congress party had been known to nurture leaders from the ground to reach the pinnacle of political power. Kamaraj, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Y.B. Chavan—all adorn this illustrious list. These stalwarts had reached the top rung of the party leadership through their competence, commitment and convictions. Chandra Shekhar belonged to this grand tradition of the Congress party that was abandoned later. If the Congress leadership had not exiled Chandra Shekhar for raising some of the most pertinent and valid issues, the party would not have come to the stage of being clueless, leaderless and rudderless in the post-Indira Gandhi era.

Chandra Shekhar’s presence would have impeded the prevalence of sycophancy, the rise of coterie culture, and the idolizing of personality cult within the Congress party. Consequently, it would have raised effective and mass-based leadership in the party. Through the imprisonment of Chandra Shekhar, the high command of the party sent two blunt messages to every Congress member—the era of genuine mass-based leaders and the progression of regional leaders was well and truly over, and nobody could challenge the absolute monopoly of the Nehru-Gandhi family over the party affairs. It was not accidental that Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao’s dead body was denied entry into the Congress party headquarters and instead of giving him a resting place in Delhi, the party ensured that his remains were packed off to Hyderabad. In this era of sycophant politics sans self-esteem, Chandra Shekhar treasured his self-respect for he believed one could not engage in politics without being true to oneself.

Chandra Shekhar was not merely a politician; he was an exceptional administrator and statesman. Before assuming the prime ministership, he had never held any administrative or constitutional office throughout his political career. However, his clear and decisive approach in tackling critical issues during his brief tenure as prime minister received the highest praise in India and abroad. Former President R. Venkataraman fondly remembered Chandra Shekhar’s tenure and stated that ‘had Chandra Shekhar commanded a majority in the House, he would have been ranked amongst the great prime ministers of India’.

On his very first day as prime minister after the oath taking, he was obliged to deliver a customary address to the nation, a speech of about twenty minutes at the state radio and television network. Former Principal Information Officer (PIO) I. Ramamohan Rao wrote in his book that Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar went to the television studios dressed in a kurta, dhoti, chappal and bandi. It was the attire he had always worn. Chandra Shekhar delivered the speech without any prepared notes and finished his speech in exactly twenty minutes. Rao remembered that it was a brilliant speech in which Chandra Shekhar gave a clear picture of the existing situation and his priorities as the new prime minister.

To prevent India from defaulting on sovereign repayments and thereby getting branded as a bankrupt nation, Chandra Shekhar took the politically suicidal decision to ship gold overseas to raise foreign exchange to salvage India’s reputation and pride. He demonstrated a rational and robust approach to resolve several contentious issues such as caste-based conflicts post the Mandal agitation, community-based conflicts post the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and insurgencies in Assam, Tamil Nadu, and Jammu and Kashmir. In those times, the national television channel, Doordarshan, held the monopoly on Indian viewers. However, the Prime Minister’s office (PMO) used to receive all the daily news bulletins before broadcast. In his very first meeting with Doordarshan officials, Chandra Shekhar gave clear instructions to discontinue this practice of seeking prior approval for the news bulletins from the PMO. Former Foreign Secretary of India Muchkund Dubey, who had the opportunity to serve during Chandra Shekhar’s tenure, considered him as ‘the best prime minister that India has remained deprived of, except for a few months’.

Know more about this iconic leader with the book Chandra Shekhar: https://amzn.to/2G0ExCR